Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging

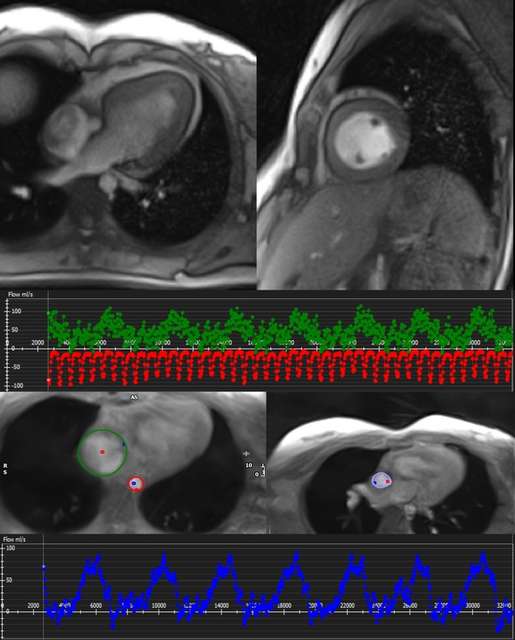

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a medical imaging technique used in radiology to generate pictures of the anatomy and the physiological processes inside the body. MRI scanners use strong magnetic fields, magnetic field gradients, and radio waves to form images of the organs in the body. MRI does not involve X-rays or the use of ionizing radiation, which distinguishes it from computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. MRI is a medical application of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) which can also be used for imaging in other NMR applications, such as NMR spectroscopy. MRI is widely used in hospitals and clinics for medical diagnosis, staging and follow-up of disease. Compared to CT, MRI provides better contrast in images of soft tissues, e.g. in the brain or abdomen. However, it may be perceived as less comfortable by patients, due to the usually longer and louder measurements with the subject in a long, confining tube, although "open" MRI designs mostly relieve this. Additionally, implants and other non-removable metal in the body can pose a risk and may exclude some patients from undergoing an MRI examination safely. MRI was originally called NMRI (nuclear magnetic resonance imaging), but "nuclear" was dropped to avoid negative associations. Certain atomic nuclei are able to absorb radio frequency (RF) energy when placed in an external magnetic field; the resultant evolving spin polarization can induce an RF signal in a radio frequency coil and thereby be detected. In other words, the nuclear magnetic spin of protons in the hydrogen nuclei resonates with the RF incident waves and emit coherent radiation with compact direction, energy (frequency) and phase. This coherent amplified radiation is then detected by RF antennas close to the subject being examined. It is a process similar to masers. In clinical and research MRI, hydrogen atoms are most often used to generate a macroscopic polarized radiation that is detected by the antennas. Hydrogen atoms are naturally abundant in humans and other biological organisms, particularly in water and fat. For this reason, most MRI scans essentially map the location of water and fat in the body. Pulses of radio waves excite the nuclear spin energy transition, and magnetic field gradients localize the polarization in space. By varying the parameters of the pulse sequence, different contrasts may be generated between tissues based on the relaxation properties of the hydrogen atoms therein. Since its development in the 1970s and 1980s, MRI has proven to be a versatile imaging technique. While MRI is most prominently used in diagnostic medicine and biomedical research, it also may be used to form images of non-living objects, such as mummies. Diffusion MRI and functional MRI extend the utility of MRI to capture neuronal tracts and blood flow respectively in the nervous system, in addition to detailed spatial images. The sustained increase in demand for MRI within health systems has led to concerns about cost effectiveness and overdiagnosis.

Read more about 'Magnetic resonance imaging' at: WikipediaWikipedia contributors. "Magnetic resonance imaging." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, March 1, 2026.